Two books from Smog Press

Founded in 2021 by Adam Ianniello & Taylor Galloway, newcomer Smog Press is a Los Angeles-based independent art book publisher. They were kind enough to send us their first two titles: Brian McSwain’s Memorare, and 37.2431° N, 115.7930° W, a collaboration between Ianniello and Galloway. Lucy Rogers and Eugenie Shinkle each chose one to write on.

Adam Ianniello and Taylor Galloway – 37.2431° N, 115.7930° W

This debut publication released by Smog Press presents the work of its co-founders, Taylor Galloway and Adam Ianniello. Taken in and around Rachel, a sparsely populated town in the Nevada desert, 37.2431° N, 115.7930° W, follows the so-called extra-terrestrial highway which winds through the landscape. Next to the notorious Area 51, a top-secret military base, this expanse of secluded desert has been the backdrop of conspiracy theories since the 1950s. First used for the development of military aircraft and weapon testing, the area now attracts UFO enthusiasts from around the world. Long since a tourist attraction, Rachel has become a site of pilgrimage for UFO hunters looking to revel in a community of like-minded individuals.

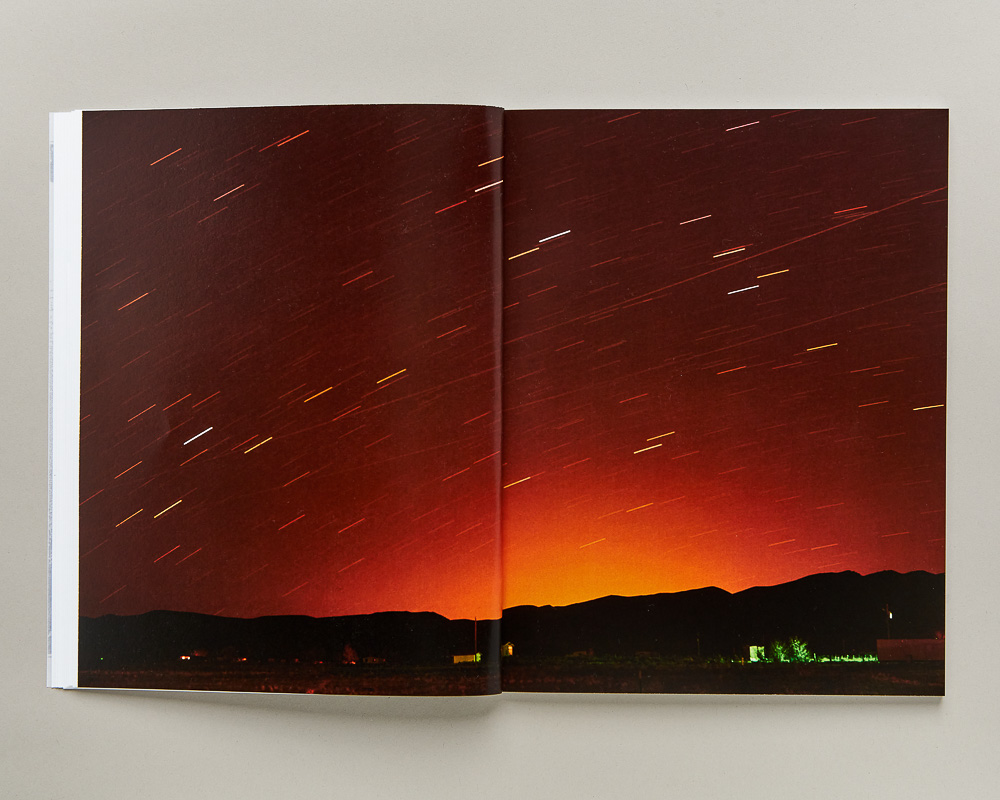

37.2431° N, 115.7930° W was made on a road trip of sorts. Travelling together to Rachel, Nevada, Galloway and Ianniello stay on location at Little A’Le’Inn, an alien-themed trailer motel. The motel, and the community of UFO hunters who stay there, form the backdrop of their images. Introduced first in the book’s cover, the motel is a motif throughout, which frames and underpins their images. Together Galloway and Ianniello play along in the search for signs of extra-terrestrial life through their photographs of the night’s sky, and rubble landscape, marked with leaked oil and scorched earth.

Photographers are too often portrayed as lone wolves or worse, in competition with one another. Here Galloway and Ianniello begin to break this mould through creating two stories from one shared experience

Though photographed in tandem, the book is split into clear two sections, flipped on one another. Even without this clear distinction, Galloway’s high contrast colour images place emphasis on landscape. They stand out against those of Ianniello, grainy and black-and-white, taken in the hours of dusk or dawn. While Galloway begins by looking out onto the landscape seen from the window of the motel room, Ianniello’s approach is more introspective. Taken in the dark, he focuses on the characters who loiter around the motel, on the kitsch models of alien aircraft and celebrity statues. 37.2431° N, 115.7930° W is full of two-page spreads which compare how Rachel represents itself and the reality; cows graze next to graffiti on a wall of a cartoon cow being abducted by a flying saucer.

The transparent vellum dust jacket – with its printed thick hand-drawn lines – reminds me of a comic book. Not the obvious cover choice for a photobook, its transparency allows photographic images to bleed through from underneath. There is a playfulness in the approach to book design, which echoes their images. Photographers are too often portrayed as lone wolves or worse, in competition with one another. Here Galloway and Ianniello begin to break this mould, creating two stories from one shared experience. Despite this, the format which divides the two approaches breaks their flow and cuts them off from dialogue with one-another.

Shot over a short period and the first publication of a new publisher, this book is a pilot of sorts, and it seems unfair to weigh it down with too much analysis. There is a humour in Galloway and Ianniello’s shared approach, a playful empathy with those who end up in these places. In the index, a single sentence refers to Rachel’s location on the land of the Newe people. It’s a telling acknowledgement and while I cannot say obvious in a tangible form, there is a sense of waste and loss. The town of Rachel, with a population of 70 people, is a non-place, an alien theme park, built on an eclectic mix of models and reconstructions, spaceships, and paraphernalia. It feels tired and neglected, a blot in a vast landscape.

Lucy Rogers

Brian McSwain – Memorare

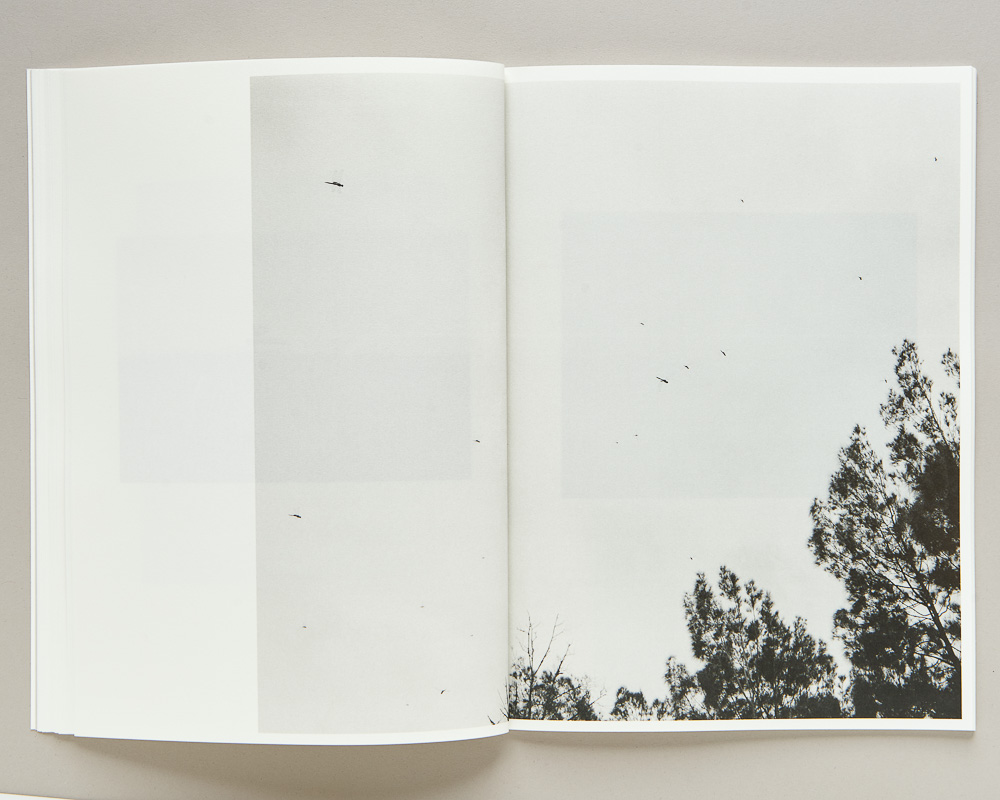

The second release from Smog Press is a book of landscape photographs, simply organised to give the impression of a loose narrative beginning in flat empty farmland, passing through a deserted town, and heading back out into the fields again. The terrain in McSwain’s images will be familiar to anyone who has spent time outside of America’s cities: cracked asphalt and long stretches of farmland, lone trees, tangled weeds and wildflowers in the fallow plots between fields. You can drive for hours in landscapes like these without seeing another person, just the repeating forms of wire fences, shabby trailer homes, empty intersections, rusting cars and ruined barns. They’re bare of people, but McSwain’s photographs teem with animal and insect life – butterflies, cicadas, frogs, dogs, chickens, a black cat crouching in the shadow of a building. There’s little to indicate exactly where we are, or when. It might just be one long day, stretching from the grey morning mist to the approaching night as clouds push over the horizon.

The terrain in McSwain’s images will be familiar to anyone who has spent time outside of America’s cities: cracked asphalt and long stretches of farmland, lone trees, tangled weeds and wildflowers in the fallow plots between fields.

If the above reads a bit like inventory of features, the experience of the book is very different. It’s slow-paced and serene, with the pleasing indolence of a road trip that has no particular destination. Visually, McSwain’s photographs lean gently on a heritage that stretches from Walker Evans through the likes of William Christenberry, Robert Adams, David Plowden and others who approach the American landscape as an elegy to a lost architectural and industrial heritage. Lately, there’s been a resurgence of interest in these quiet vernacular landscapes, but younger photographers working in this idiom seem less invested in melancholy and loss, and more likely to view such places through the lens of personal attachment – think of Tim Carpenter’s Christmas Day, Buck’s Pond Road, or Rahim Fortune’s Oklahoma. And indeed, in the epilogue, we learn that most of the photographs were shot in Florida’s Palm Beach County between 2015 and 2021 – a landscape that McSwain knows well, and drove through many times in the months before and after the death of his mother.

Such landscapes can seem bleak, and McSwain’s austere black and white photographs don’t attempt to show them as anything more or less than they are. The reality of life in rural America is far from easy, especially now, when the temptation to be somewhere else is so strong, and so difficult to avoid. Rather than a lament, though, Memorare is an embodiment of the contradictions that such places represent. For some, the anonymity of modern urban life is a welcome alternative to an insular and blandly uneventful small town existence. For others, the open terrain outside cities is endlessly varied and changeable; landscapes that appear empty to the outside eye are bursting with life if you know how and where to look. And as McSwain observes in a short text at the back of the book, in places like these, where nothing ever seems to change, there’s solace to be found in the simple fact of their persistence. A beautiful balance of poignancy and sweetness, Memorare gets better each time I pick it up.

Eugenie Shinkle