Smaller Is Better – Aaron Stern’s Polaroids, Small Prints and Ephemera

In Vilém Flusser’s Towards a Philosophy of Photography he describes photographs as harbingers of the post-industrial information economy – their value as unique objects is negligible because what is of value is the information they carry. In the digital age, this takes on an even greater significance because most photography now exists without ever being mechanically reproduced. Photographs can now be made, consumed, and distributed without coming into physical being.

Polaroids, Small Prints and Ephemera, at London’s Webber Gallery,counters this tendency. Collaged on walls and tables, fixed under thick plexiglass, and positioned at incongruous heights, works are arranged to encourage visitors to consider them not only for their descriptive and pictorial qualities, but also their physical ones – size, weight, and texture. Initially conceived for Anent Gallery in Mexico City as part of Zona Maco, curator Aaron Stern’s exhibition is restaged at Webber Gallery in London with original artists Daniel Arnold, Gray Sorrenti, Irina Rozovsky, Jerry Hsu, Mike Brodie, Mario Sorrenti and Vince Aletti. This iteration also includes Laurel Thoma, Chris Rhodes, Jeremy Everett, Juan Brenner, Dexter Navy, Laura Jane Coulson, Alexa Chung and omits works by Pia-Paulina Guilmoth, Rafael Prieto, Shaniqwa Jarvis and Nicole Della Costa, which were part of the original show.

Stern’s artists reconsider how photographs might establish presence. Their work is small, intimate, fallible and personal.

Photography’s struggle for presence is nothing new. From the late 1970s onwards, in a moment defined in Michael Fried’s Why Photography Matters as Art as Never Before, photography’s aspirations towards the presence of painting were addressed through scale and finish. Intended for the gallery wall, Jeff Wall’s large, expensively made, tableau style lightboxes epitomise this turn. It’s an approach which has helped elevate photography’s status as an art form in institutions but with the unintended consequence that it has created a benchmark for showing photography which is difficult and expensive to reach. As the show’s curator Aaron Stern notes: “Recently I asked a gallerist I know who used to show a lot of photography why he doesn’t anymore, and he answered that working with photographers was a huge pain in the ass. Everything has to be printed like this, framed like that. There are four to six rounds of proofing. They’re so overly precious.”

Stern’s artists reconsider how photographs might establish presence. Their work is small, intimate, fallible and personal. The photographers’ hand in their work is clearly visible: images are made not taken. Mario Sorrenti photographs the vast collages of print layouts, contact sheets and snapshots with handwritten captions which covered the walls of his Chrystie Street loft as part of the 2004 installation The Wall – 15 years of work contained in seven unique 5×4” instant prints.

Elsewhere, Juan Brenner presents a series of twenty Polaroid photographs of costumed friends against a white wall. Displayed in two rows of ten images, they depict his subjects’ upper and lower halves – a structure which is quickly abandoned as participants spill into and out of frame, fail to connect their heads to their torsos, and form hybridised bodies with fellow subjects. Playful, funny and imperfect, they are intimately tied to the form and immediacy of instant film.

On the opposite wall are Mike Brodie’s Polaroids – made under the moniker Polaroid Kid while hopping freight trains from his late teens onwards. A man peeking over a barrier, a hand cradling a plastic baby, a mouse caught by the throat in a trap in an image so vivid its cries are nearly audible, a grave marked by a wooden cross made with two-by-fours and inscribed in black marker, and a portrait of a young boy with bright red hair. Seemingly shot on expired or faulty film, the portrait’s top right corner, similarly ginger, is unexposed. The boy clutches a children’s book, Spiders and their kin, and stares into the lens. His facial expression is asymmetrical: the right half is almost blank, open to the world. On his left, he adopts the expression of an older man – furrows his eyebrow and squints his eye. It feels at once like a testament to the curiosity which propels the freight-hopper and a memento of his fading innocence.

Showing equally personal work, Alexa Chung is an interesting addition to the show. Best known as a model and media personality Chung, a long-time friend of Stern, exhibits images taken with no intention of being shown publicly. Displayed in the form of a sprawling collage, made collaboratively with the show’s curator, Chung’s photographs alternate between her public and personal life – Karl Lagerfeld’s head in side profile, a selfie in the bathroom at the Met Gala, portraits of friends and strangers, the words “fuck you” written in the sand.

Most interesting are Chung’s portraits which contain none of the formal rigidity, artifice and occasional malice of editorial photographers or paparazzo. Her work, which must be informed by time spent on the other side of the camera – something which becomes particularly apparent when she shoots back at a horde of photographers pointing their lenses at her – values photography as a medium which can capture intimacy, memory and humour. The content and form of Chung’s photographs are reminiscent of the 6×4 prints you get after developing a roll of film at a pharmacy, evoking the nostalgia of leafing through old snapshots.

It’s undeniable that to an extent Stern’s show relies on this kind of nostalgia to conjure objecthood. Showing work made using analogue and in some cases obsolete formats, many Polaroids in the show are made on the now discontinued Fuji FP100C, which gives the work a feeling of historicity – raising its status from photograph to relic. This feeling of historicity is however inherent to certain works – in pictures by Sorrenti, Brodie and Brenner, in Jiro Konami’s instant photos superimposed on top of a monochromatic darkroom print, Chris Rhodes’ surreal fragments from everyday life caught on instant film, and Vince Aletti’s collage of images of the male form torn from the pages of newspapers and magazines: magnified under thick plexiglass, they appear to be bulging with stopped time. The result is what Stern refers to as a kind of “snow globe” effect. Used to frame a number of works in the show, it is particularly effective with the Polaroids, which, thanks to their iconic white border, already have the appearance of being a window into the time they depict.

Showing work made using analogue and in some cases obsolete formats, many Polaroids in the show are made on the now discontinued Fuji FP100C, which gives the work a feeling of historicity – raising its status from photograph to relic.

There are, however, artists whose work documents what Stern describes as the “tumultuous” present. In a series of quieter images than the chaotic vignettes of street life in New York typical of his work, Daniel Arnold presents stolen moments from everyday life which feel equally timeless and contemporary, albeit shot on 35mm film. Wind whips snow across the frame of a street scene, a figure waits at a pedestrian crossing as its red hand blends into the bright lights of illuminated offices in the city’s highrise buildings, a silhouette kneels in front of a Christmas tree which bathes the room in a rose-tinted hue. They adopt a chiaroscuro akin to that of classical painting and make an argument for the use of analogue technology beyond its nostalgic associations – its dynamic range offers, in my opinion, a more accurate rendering of the density and shadow of reality than its digital counterparts.

Nearby, in a series of hallucinatory images, Jerry Hsu toys with photography’s ontological properties. Hsu, whose two monographs to date have both been books of photographs made on mobile phones – the blackberry and iPhone respectively – presents a series of images shot on film which play with the construction of reality. Bunches of flowers appear in a soft blur which reduces them to their colours and basic forms, a pink rose made of buttercream sits perched on the edge of a knife, a car stopped in the middle of the street is engulfed in flames and billowing black smoke. Hsu’s work feels obsessed with depicting rather than making sense of the madness of the present. He adopts a Weegee, nightcrawler-esque, approach to making images: spending hours wandering the streets and using the Citizen app to locate chaos. This tension crystalises in one image, in which we look down at what we assume is the photographer’s hand – echoing a technique used by oneironauts, so-called ‘dream travellers’, who look toward their own hands in dreams to activate lucid sleep.

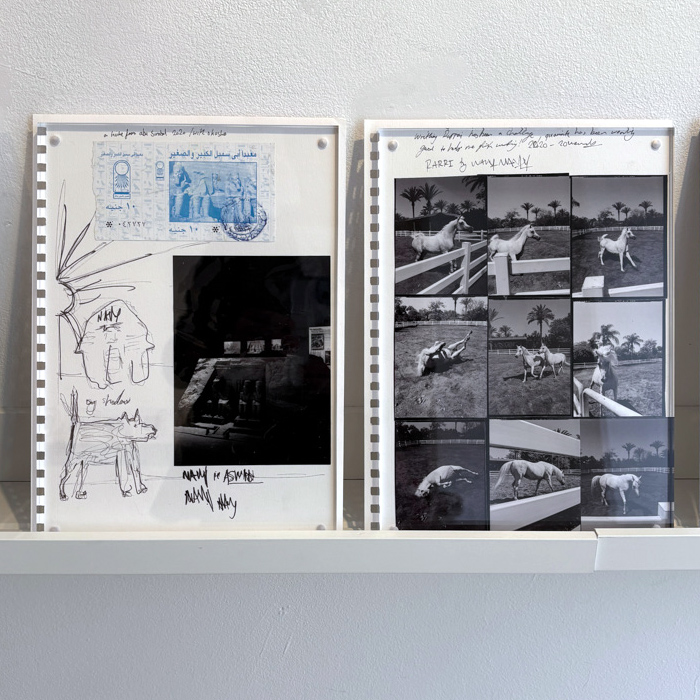

This struggle for presence in an age of digital immateriality is best summed up for me in a typology of images of four boys by Dexter Navy. Navy shows collaged, annotated and illuminated pages from a spiralbound notebook encased in magnetic glass frames: jigsawed photographs of a man on horseback recreated in sketches below, images of Egyptian monuments and a ticket from Abu Simbel, contact prints of horses running and falling in a paddock, a sequence of images made by the photographer’s father sellotaped to the notebook’s leatherette back cover with the handwritten caption: “here is my father he is 19 & moved to Iraq from Egypt. I found these images negs 40 years after he shot them.” A sequence of the same square format black and white portrait of four boys is cropped closer and closer. Three of the boys, engaged by some mechanical object in the foreground, are obscured from view as the portrait repeats, zooming in on the fourth subject who sits back from the others, turns to look into the camera and rests his chin in his hand. The picture is enlarged until what once looked like an analogue photograph is replaced by a pixelated image of his near black pupil and iris and the white of his sclera, on which the word عين (eye) is written in pen.

The small print has its origins in the very earliest forms of photography – the carte de visite: greeting-card sized self-portraits of friends, family and celebrities which were collected and traded in the 19th century, now thought of as an early form of social media. Their popularity reveals something intrinsic to human nature – the impulse to save, to record, to store, the desire to try to stop time, the need for the tangible and the real, the need for something to hold on to. As the material world seems to slip through our fingers it’s a need that only grows stronger.

Aaron Stern, Polaroids, Small Prints and Ephemera is at Webber Gallery in London until 31 July 2025

banner image: Alexa Chung