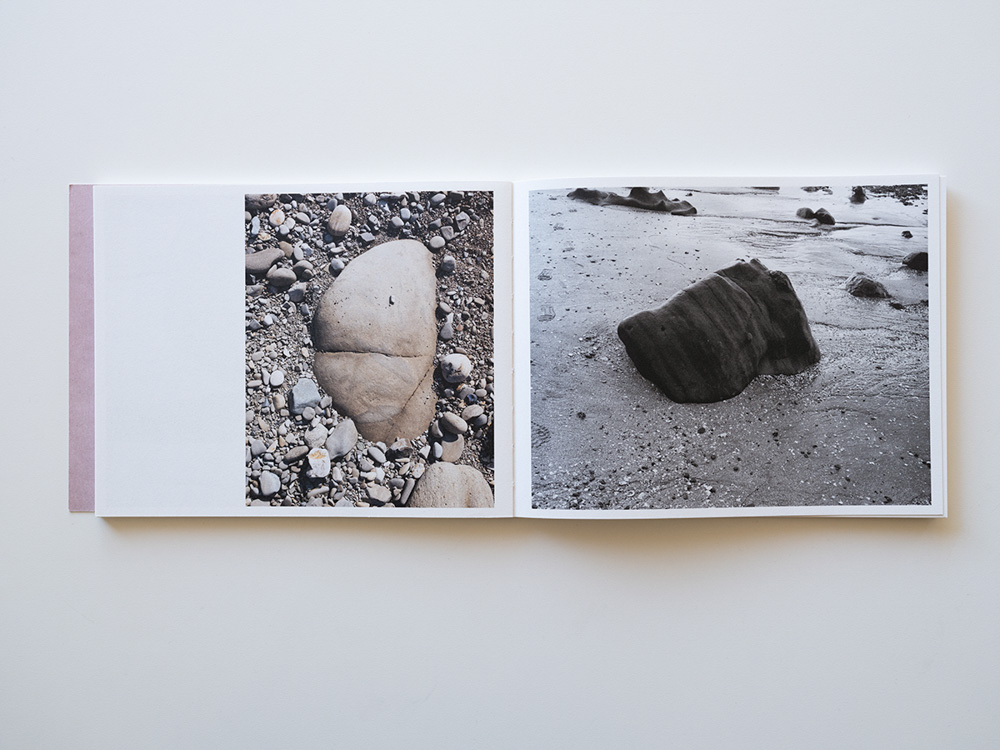

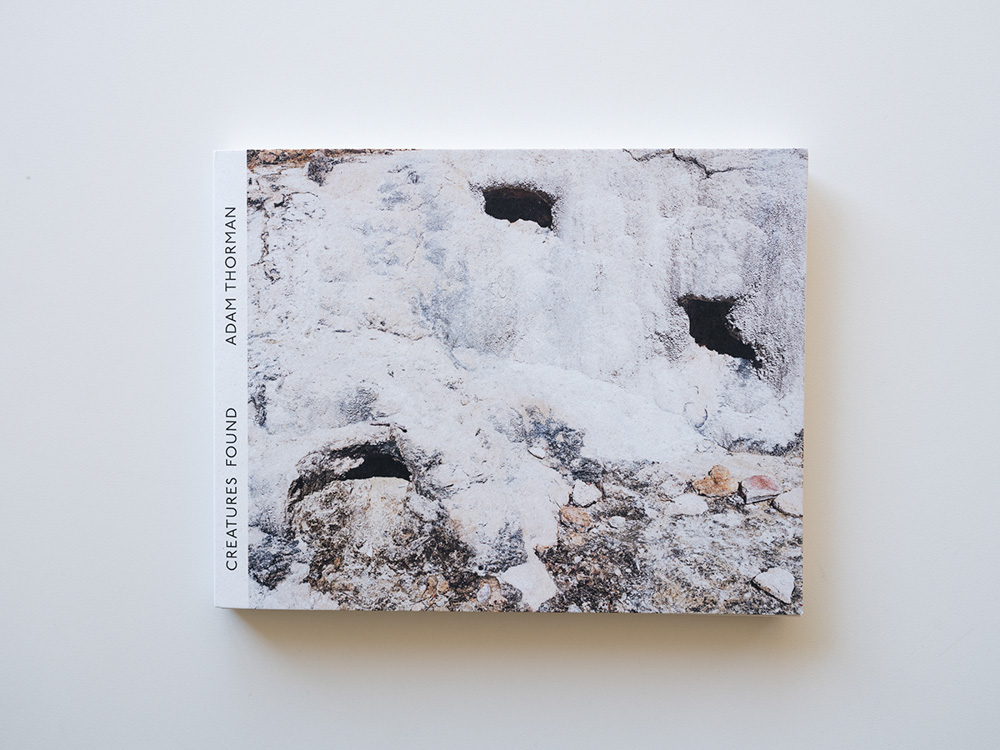

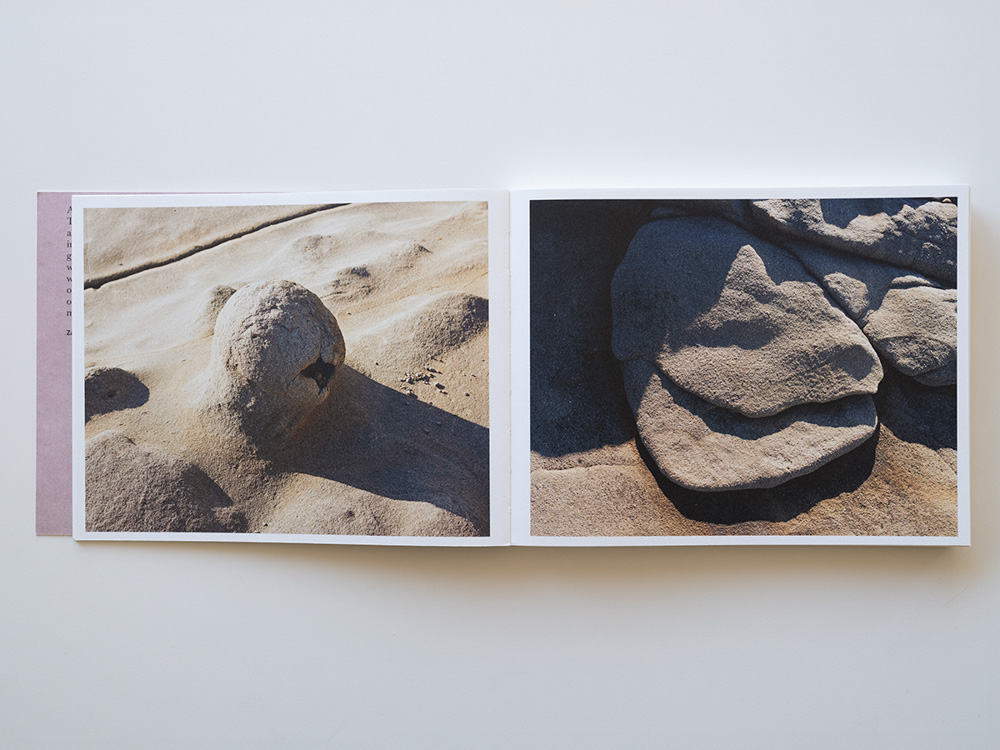

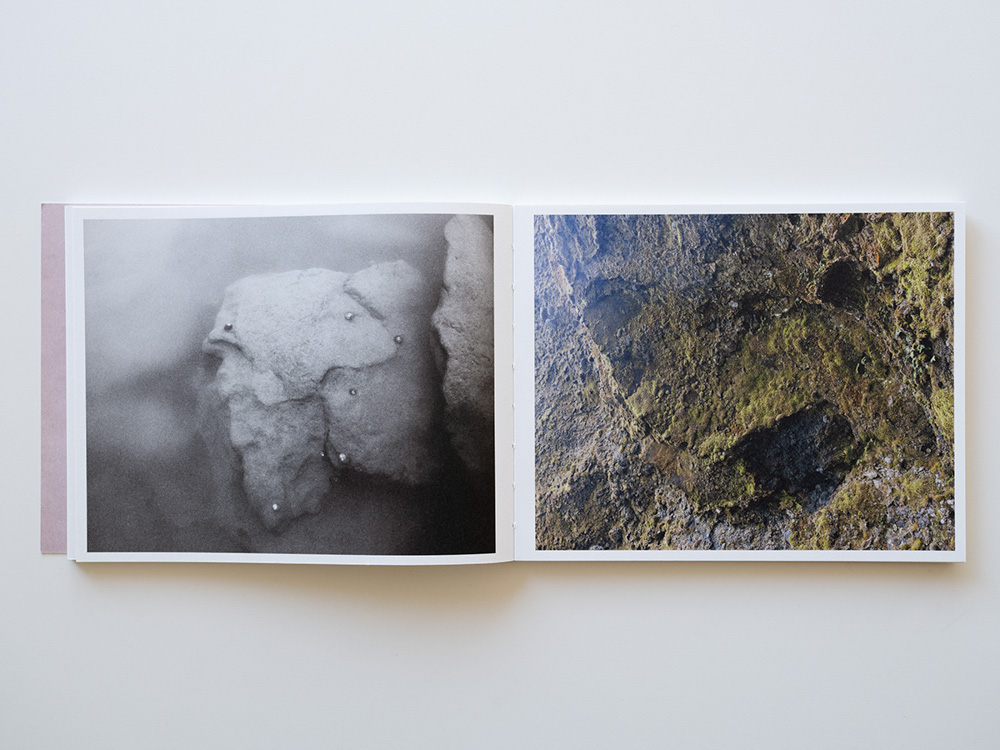

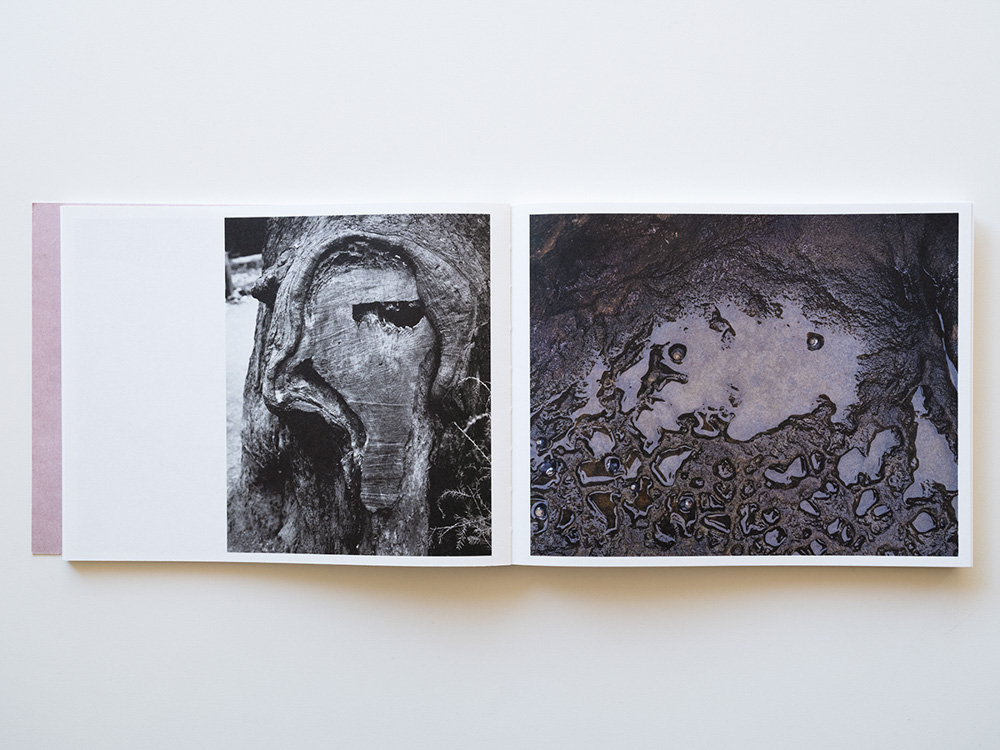

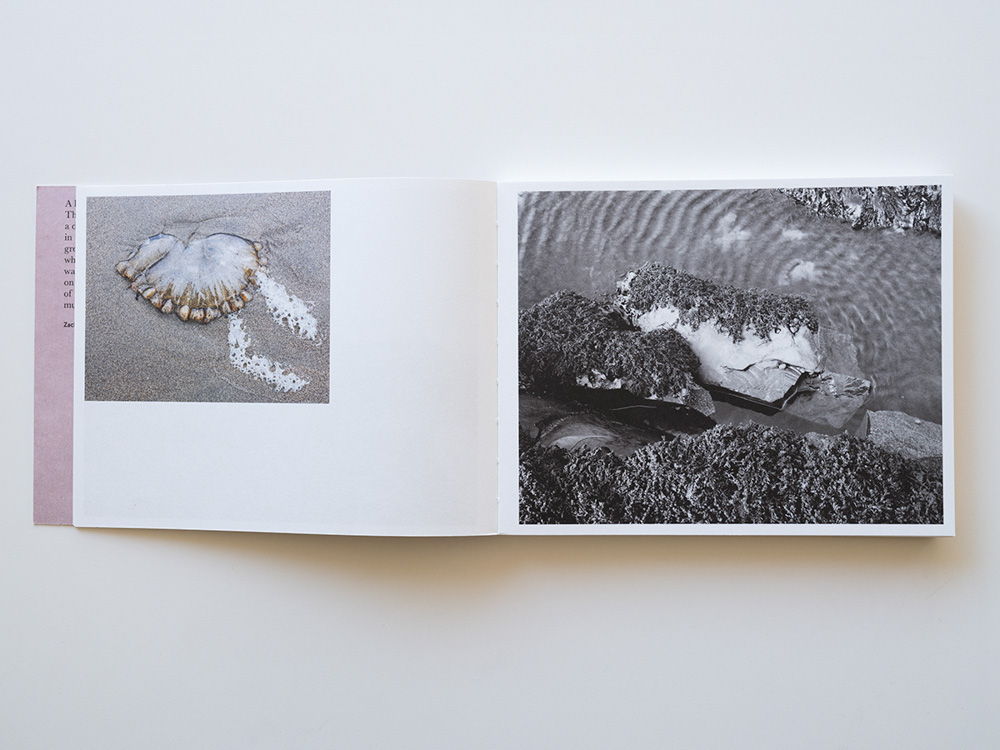

Adam Thorman – Creatures Found

Adam Thorman’s new photobook Creatures Found is a playful inquiry into the concept of pareidolia, the common perceptual phenomenon that triggers the identification of faces on inanimate objects and surfaces. In this interview with Arturo Soto, Thorman discusses his creative process, detailing how the work developed over several years and reflecting on the challenges of sequencing and structing a visual narrative.

Arturo Soto: What prompted the series Creatures Found? When did you become aware that you looked at the world in terms of pareidolia?

Adam Thorman: Creatures Found represents the core of how I see the world. I have an imaginative, metaphorical brain and have always looked at things and imagined what else they could be. I don’t even remember what I was thinking about when I made the first images that would become Creatures Found. I had just moved to Tempe, Arizona from the San Francisco Bay Area to go to grad school at Arizona State in the Fall of 2006 and I was wandering around my neighborhood making images, trying to figure out what sort of work I could make in a new place, and they started appearing. I made three creature images that Fall, two of which are in the book, and without outwardly looking for them, would find new ones periodically over the next 14 years. It wasn’t until 2020 that I became more intentional about looking for them and the project grew exponentially over the last four years.

Creatures Found represents the core of how I see the world. I have an imaginative, metaphorical brain and have always looked at things and imagined what else they could be.

AS: Did the pandemic play a role at that stage?

AT: Yes, it did. I visited Joshua Tree National Park for the first time in mid-February 2020 and saw creatures everywhere. After a short two days in the park photographing, I came home with a huge batch of images to process, most of them potential creatures. As I sat at home during lockdown in March and went about working through the recent images I’d made, I saw that I had doubled the size of the project and that with some concentrated effort I would be able to flesh it out into a full series. With everyone staying home, the freeways were empty, so I could easily drive all over the Bay Area to take pictures, sometimes even just in a free period between my virtual classes I was teaching. There were so many things we couldn’t do at that time, but parks were outdoors and mostly empty, so it was a way I could safely make photographs. I thought of these as “creature hunting” trips. I went to Muir Woods one day and on another day went down to Santa Cruz and Natural Bridges and then drove up the coast stopping at a number of beaches, looking for creatures. Between the Joshua Tree pictures and what I was able to do during lockdown, this small side project grew into a full body of work that I then continued to add to regularly over the next four years and I still can’t stop seeing them.

AS: Do you think of your book as an archive, and if so, what’s the rationale behind it?

AT: I haven’t thought of it as an archive before. I thought of it as a possible field guide for a long time, which is related, but the term archive has never come up in how I think or write about the work. I think more about letting the viewer’s experience define the series than the nature of the collection.

AS: I’m intrigued by your use of the term field guide, which implies that these images have a defined purpose, and yet you also want the work to be open-ended.

AT: Since I made the first images when I had just started grad school, I was trying to figure out what the work was while showing the nascent work in the not-always-friendly environment of school critiques. I learned that when I named the creatures I saw, people would react to them based on whether they agreed with what I said they were and not to the image itself. The idea of a field guide was one I tried out at the time, but I moved on from the idea when I realized that I wanted the images to be more open for the viewer to interpret instead of being static and set. With narrative text in an imaginary field guide, the images would become just illustrations of the text. At the same time, I felt that a book with some vestigial field guide references, but no text, can help set the framework of discovery while leaving the narrative creation to each viewer, keeping the images open.

AS: It seems to me that the specificity of place does not have any bearing on the work. Do you agree?

AT: I do agree. My goal is to make images that are descriptive, while still having elements of abstraction, and part of that goal is to have an experience of the landscape that is specific to the features you can see without being specific to a place. There are only a few horizons in the book that properly place the images in recognizable locations. One creature in the book is a rock I’ve seen in a few other photographers’ images, so I know at least some locations are identifiable, and I don’t mind that, but I’m not looking to make location a central part of the reading of the images. Being from the San Francisco Bay Area, a number of the images in the book are from here. Those images will probably read as “Northern California Coast” to those who have spent time here, even if not that specific rock and that specific beach may not. Many of the images have so few points of reference that only a particularly observant regular visitor to that specific spot may be able to identify them. I’m not trying to obscure the location, but the location just isn’t central to being able to understand what the images are about in this context. Some of the images were taken in very meaningful places to me, which adds a layer of meaning when I look at them, but I like that the images will have different lives for different people.

My goal is to make images that are descriptive, while still having elements of abstraction, and part of that goal is to have an experience of the landscape that is specific to the features you can see without being specific to a place.

AS: What was your methodology for sequencing the pictures?

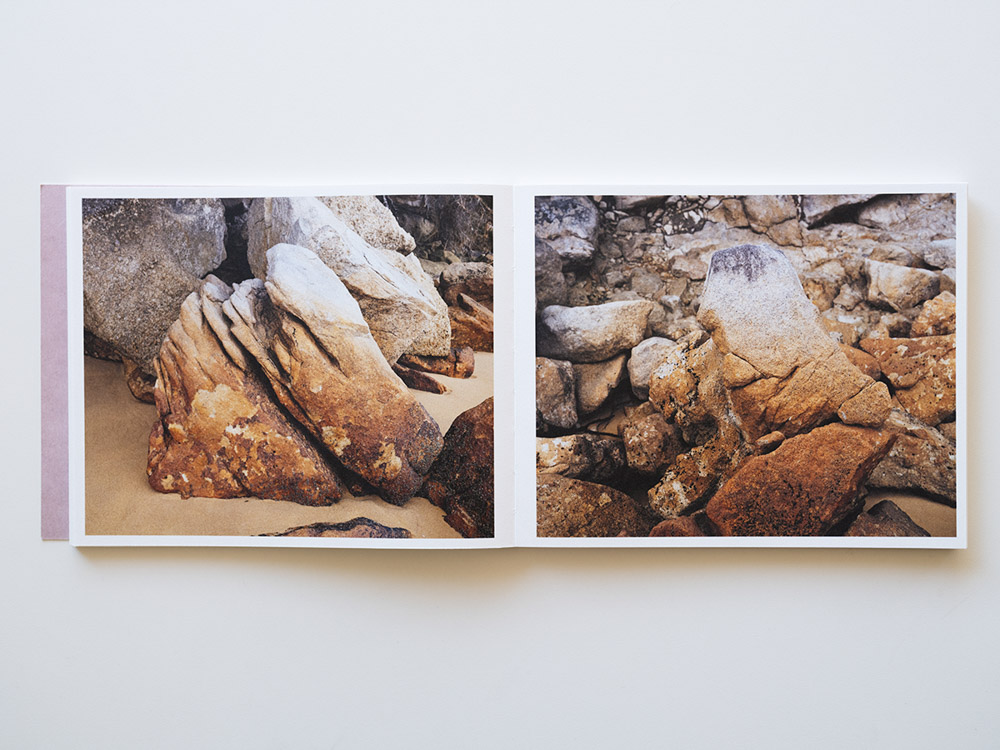

AT: The sequencing was done in collaboration with Rob van Hoesel, one of the co-publishers of The Eriskay Connection. I had initially submitted a book dummy with around 60 images, but Rob wanted to sit with my full pool of 130 images and do his own fresh sequencing of the images to create an initial design of the book. We used that initial design as a starting off point and then went back and forth about the theory of organization for the book, relationships that worked and that didn’t, and images that should be added or taken away. It was my favorite part of the process, being able to dig into the image sequence in a deep, collaborative way. There are elements of both of our ideas in the final sequence, and while some of my favorite parts of the book are things that I wanted to make sure were in the book, others are relationships Rob saw that I hadn’t previously considered. I like that there are loose sections of the book grouped by type of place, which was how Rob initially organized it. At the same time, it was important to me that the pairs not be reductive and obvious, and I wanted to break up some of the pairings of like things. The last addition to the book, though, was the pair of orange-to-gray ombre rocks that were taken in the same spot, less than a minute apart, during a trip in March (which I rushed to process out and send in while we were already deep into working on the sequence) and requested that they stay together as a spread. I didn’t want any one rule of sequencing to make the book feel predictable.

AS: It took you eighteen years to complete this body of work. What was the effect of time on the series?

AT: It had a lot less effect than I had thought it would. I was pretty shocked at how consistent my vision has been throughout the 119 images from between 2006 and 2024 collected in the book. I was trying to count the number of cameras in the book, and there are at least 6: two 6×7 film cameras (Bronica and Mamiya) shooting both color and black and white film, three high-end digital cameras (two Nikon, one Fuji), and at least one iPhone image from 6 or so years ago (I’m pretty sure that no one will ever figure out which image was taken with a phone), and I may have missed one or two other cameras in there. Throughout the time I’ve been making these images I worked on numerous other projects, including a period where I fundamentally changed my approach to how I make images, and another moment where I made a switch from shooting predominantly film to predominantly digital photographs. Given all of that, I was surprised at how consistent the images in this project are when I was working on the book. Oftentimes I am out in a location taking very different kinds of images for a specific project, when I find a creature and make an image of it before going back to what I was doing. It wasn’t necessarily a conscious decision to change how I photographed, it’s just how I capture the creatures. Whenever I’d go to process my new images (film or digital), I would first scan or work up the creature and toss it in a Creatures Found folder before going back to whatever other project I was working on. Sometimes I’d find several and other times there would just be one and those would appear infrequently. In the end, it seems that this book represents a foundational way of seeing for me, the root of my photographic eye.

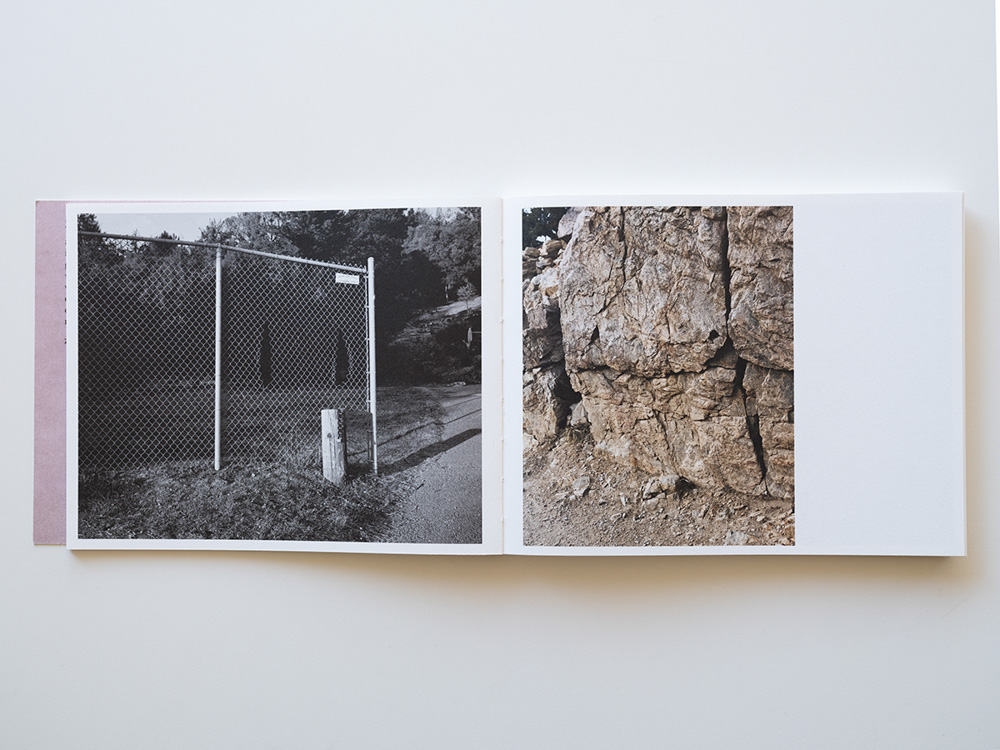

AS: The book includes a few pictures of interiors and other non-natural aspects of the world. Why did you decide to include these?

AT: At its core, this series is about finding the animate in the inanimate, and over the years I’ve found creatures inside as well as outside. I love the interiors and exterior non-natural objects and wanted to find a way to include them, if possible, even though they’re a small subset of the series. I felt like I had enough of them and initially had them peppered throughout, but Rob tried making a little group of them, and I thought that worked really well. It might have been a more cohesive series without them, but I feel like it’s a more interesting series with them.

AS: It can happen that viewers don’t immediately recognize a face in these shapes, but the pictures’ compositional variety gives them quite a bit of latitude to see something else or even project what they want onto the images. How do you reconcile your subjectivity with an open-ended reading of these images?

AT: The reason I’ve chosen to not title my creatures is to intentionally give the viewer this open experience of their own discovery. It was important to me that the book had a variety of what I thought of as more obvious and more subtle images in the series. It has been interesting to discover that some of the images I thought were obvious are completely opaque for viewers. If the whole series were obvious, it would lose interest to me. The ones that aren’t obvious but feel creature-y are the key images for me. Without them the viewer could too easily run through the images ticking off the recognized creature not stopping to think. While every image does have something specific that I saw in it, once the images are out in the world, I want them to be reimagined and claimed by each viewer. What I see in them no longer matters. I see the book as me creating the conditions for the viewer to make their own connections and stories for the images.

At its core, this series is about finding the animate in the inanimate.

AS: Given that this is a playful project, what do you think of the role of humor in contemporary art?

AT: I think that art should encompass the full range of emotions and reactions. My definition of art is simple: there needs to be metaphor, with more than one meaning to the subject, and you have to be intending to make art. As long as there is metaphor, I would hope that artists are exploring every kind of human experience. I have a maximalist approach to types of art. The more variety of types and voices, the better, and good art can be made in any genre. Too often “genre” work is devalued as unserious. I think of Creatures Found as a playful experience, but also a serious landscape book at the same time, and I don’t see those things as contradictory.

AS: Was there anything that you wanted to include in the project but couldn’t?

AT: Having worked on the project over such a large amount of time, there have been several different forms of the project at different times. The poem by Zachary Schomburg that opens the book is one of fifteen creative pieces that were created in response to different images in the series. I approached some of my favorite writers during lockdown in 2020 to invite them to collaborate and create an original piece about an image of their choice and I had a version of the book with a much smaller edit of images alongside the fifteen image/text pairings. There was a loss in not being able to include all of the writing and songs in this book, but the gain was a more thoughtfully sequenced, full photography book and I’m really happy with where it ended up. The other thing that didn’t end up in the book was one of the early, important images in the series. It’s an image from 2008 of Strokkur, the famous giant geyser in Iceland, where the huge plume of vapor is in the shape of a giant rabbit. I took the image on a small Canon Elph point and shoot and even though it had been a core part of the project since the beginning, Rob and I agreed that it just didn’t fit in the final edit no matter where we moved it, so it didn’t make the cut.

AS: How did you experience the differences between showing Creatures Found on the wall and as a book?

AT: I’ve always envisioned the series as a book first and have only shown Creatures Found formally once, as part of a group of events around the theme of Monsters at Helix, a pop-up space run by the Exploratorium, a San Francisco science museum, in 2014. Individual creatures have appeared in other series, with a new creature on the wall in my solo show in Mexico City in August 2024 at 8×10” alongside larger, more abstracted and altered landscapes. While the experience of some of the images would really open up at a larger scale (I exhibited the images in 2014 at 16×20” and I exhibit my photographs at sizes up to 43×54”), for the book I wanted the viewer to have a more intimate, personal experience of the creatures and I believe the smaller scale of a book you can easily hold in your hands accomplishes that well. This isn’t to say I wouldn’t love to show them at larger scale in a gallery at some point. The book was just the primary experience of the series I was focused on first. I would imagine some of the creatures will take on more a presence at larger-than-life sizes and now that the book is out, I can start to explore how scale might affect the reading of the images.

Adam Thorman

The Eriskay Connection 2024